An interview with illustrator

David Biskup

Posted: 29th September 2020 | 7 minute read

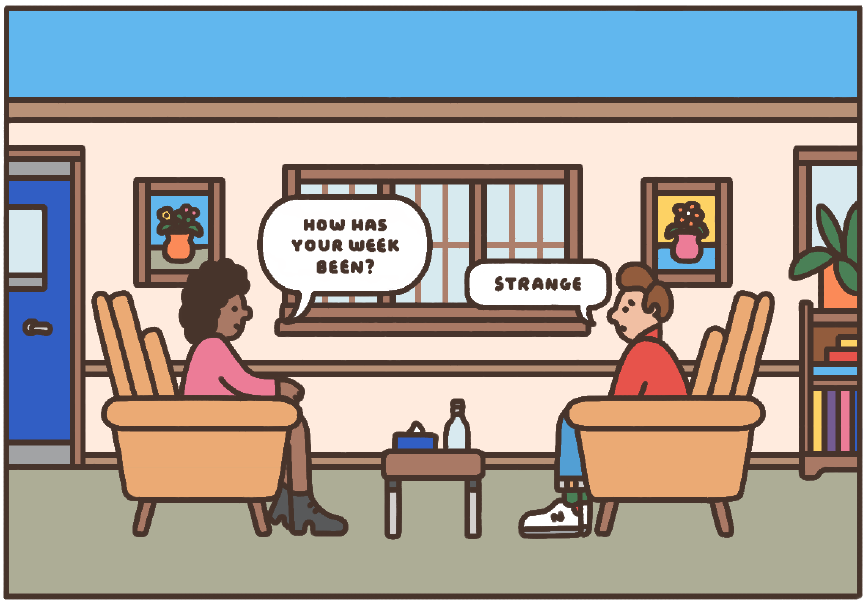

David Biskup is an Illustrator and Cartoonist from London. David has worked for an impressive range of international clients, including The New Yorker, The Guardian, Apple and Stella McCartney. Alongside his everyday practice, he also writes and draws literary comics

'There’s Only One Place This Road Ever Ends Up' is David’s most recent publication; released in September, only a year after receiving the 2019 ELCAF x WeTransfer Award.

We caught up with David to ask him a few questions about his new book, his experience writing it and why he hopes it will help others.

Just Us: Tell us about your new book and what inspired you to create it.

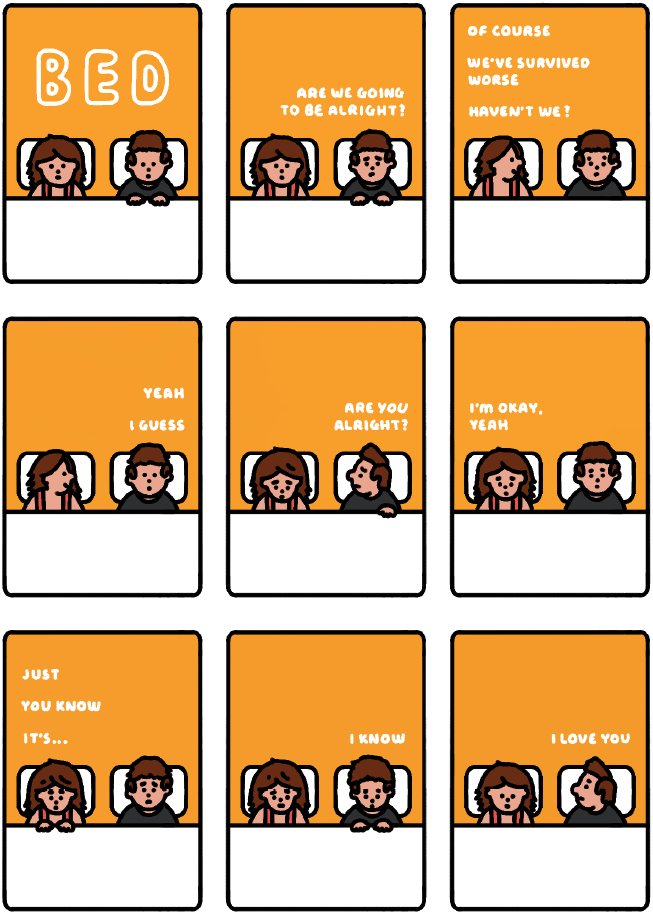

David Biskup: There's Only One Place This Road Ever Ends Up is a very personal retelling of some of the events over the past few years in mine and my fiancée Hannah's life together. Following a routine medical procedure that went badly wrong a year or so earlier, her bladder more or less completely stopped working in 2018. There was a period of about six months when no one knew what was wrong with her and we were in and out of hospital every other day. After a while we slowly began to realise that things weren't going to get better. The book represents this period when we were trying to come to terms with this altered reality of Hannah being newly disabled, unable to work, in chronic pain and needing to have surgery every few months for the rest of her life.

I wanted to tell our story because I don't think it was a one I'd necessarily seen represented much in the wider culture. You might see something about a young(ish!) couple in which one of them dies, but I'm not sure I'd seen anything about coming to terms with disability and chronic illness in the way that we have had to.

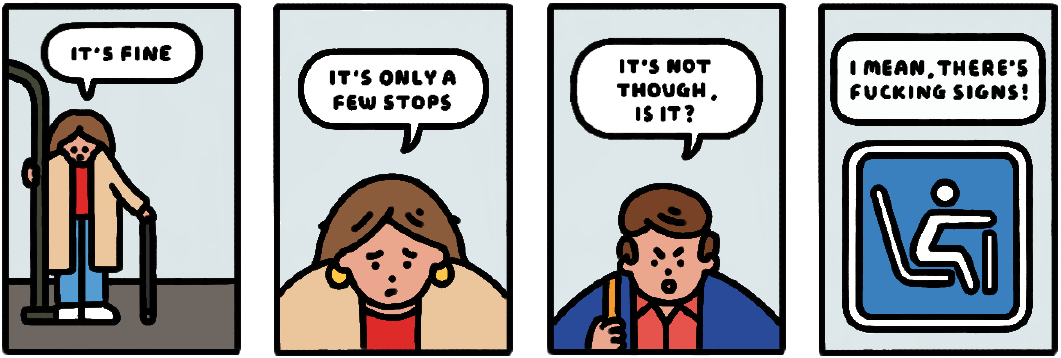

Having to relearn to navigate the world as a disabled person has been eye opening for both of us. Tasks that we would previously have considered entirely mundane and un-noteworthy, such as travelling on public transport, suddenly became stressful and sometimes dangerous. This wasn't something I had any awareness of before Hannah's illness and it's become something I feel very strongly about since. One of my aims with the book was that after reading it people might think a little more about how they interact with the world and whether there are things that they are doing without realising that make things harder for those who aren't able-bodied.

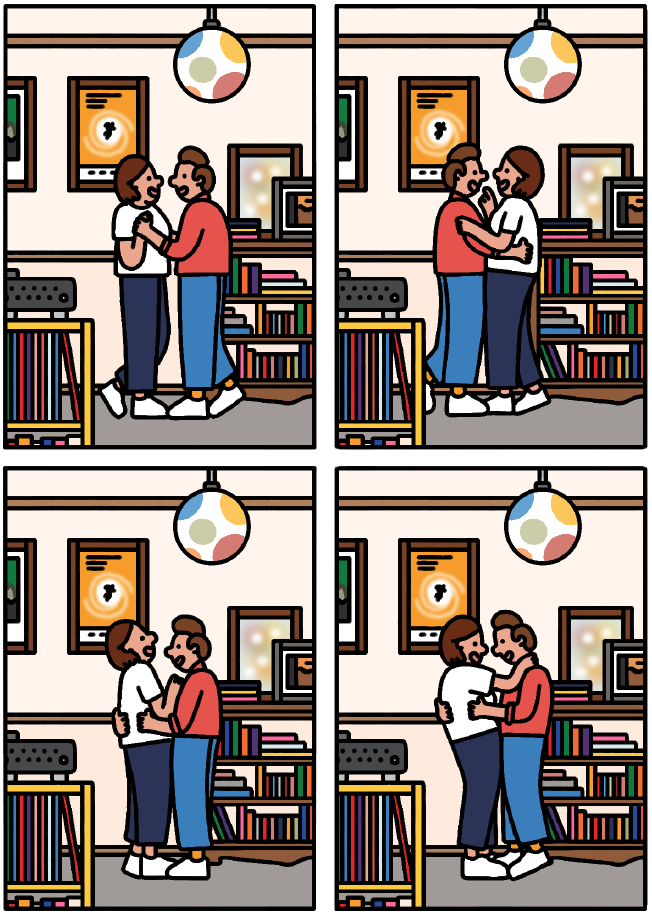

Having said all of this, I really didn't want the book to be all doom and gloom! Above anything I wanted it to be a love story and one of mundanity, day to day companionship and affection triumphing over adversity.

JU: How long did it take for you to piece it all together? Did you write, or begin to put things together during 2018-19 while events were occurring, or was it purely retrospective?

DB: Each time something life changing and traumatic happens to us (annoyingly frequently over the past five years or so - I'm only in my early thirties - whoever's programming this shit needs to calm down for a few years please!) I'm pretty adamant that I don't want to use it as fodder for my work. It seems to take a little while of things being a bit more stable (and probably honestly a few months worth of talking therapy) before I decide that it might actually be worth addressing it in my work. Luckily I've written a diary every day since 2013 so I had a lot of reference material to look over once I did actually start piecing together the story.

In terms of writing I probably spent about two months just looking back over old diary entries and making notes on them. From there I began to categorise all of the different things I thought I might want to include, working out what was traumatic, emotional, heartfelt, funny etc. Then there would have been another couple of months of working out how to structure the book in terms of the rhythm of not having a load of traumatic scenes all stacked on top of each other and making sure the pacing worked. After that I could begin writing (and then another couple of months afterwards start drawing!)

"One thing that appeals to me is the complete autonomy of the Cartoonist."

JU: What do you think comics do differently as a storytelling platform rather than say, a short story?

DB: As with any medium I think there are positives and negatives of working in comics. One thing that appeals to me is the complete autonomy of the Cartoonist. Being in control of the research, writing, pacing, structure and visuals means that the end product is almost entirely a product of your own vision. This can be a good thing or a bad thing I guess. With a novel or short story the reader has more room to project their own experiences of the world into how they visualise what is going on, whereas in a comic the imagery is slightly more prescriptive. My visual work being quite simple and graphic is an attempt to override this slightly. The more simply drawn a face is, for example, the more likely the reader is to project their own feelings and experiences onto that character and the higher the likelihood they will empathise with the story, or at least that's what I hope!

In some ways I think a comic, or at least the way I write comics, is closer in nature to writing a play. A lot of the process of writing the dialogue, particularly with this book (and with the regular strip I have in the film magazine Beneficial Shock) feels similar to writing a script. Increasingly over the past few years my emphasis has shifted towards writing dialogue. This was quite a conscious effort with this book as I felt the conversations (sometimes mundane and sometimes big) between Hannah and I were the thread that bound the whole thing together.

JU: The story feels like it was a way of processing what happened and it sounds like making a comic about painful events would be a cathartic experience, how did you find it?

DB: I have an (entirely unsubstantiated!) theory about this. My previous book Seagram was about Hannah's Post Traumatic Stress Disorder following an attack and focussed on her rehabilitation after a suicide attempt. I found that the process of writing and drawing the book had a strange affect on my memories of that period in our lives. Now when I think back to particularly traumatic events from that summer I find that more often than not the memory I'm playing over in my mind is my drawn version of it rather than the actual event. I'm starting to find a similar thing is happening with some of the things I've written about in this book as well. My pseudo-psychiatric theory is that the process of writing, roughing out the drawn version of the event and then redrawing it again and again for the finished artwork has some kind of erasing and rewriting affect on those traumatic memories. I think something similar to this happens when you have a good amount of talking based therapy focussed around trauma. You are able to re-contextualise things that have been causing you distress and occasionally have those 'break through' moments that can seem so far fetched when you see them represented in films and books but which actually do seem to happen in the same cliched way in real life. This may be complete bunkum and it's only from my own experience but I do think the experience of working on both books has helped me a lot.

JU: The funny mini-narratives are like small islands of respite between emotionally challenging events, did humour help? If so, how?

DB: It was really important to me when writing the book that it didn't just become a 'poor us' pity party and that there was enough smooth to go with the rougher passages. As anyone who has been through similar experiences with loved ones who are ill or dying will know, humour is often one of the most important coping mechanisms. A lot of what I remember from that first year or so of Hannah being ill (when our lives seemed like a non-stop tour of London's various A&E departments) is the stupid conversations we would have at 5am while she was in abject agony and waiting for a bed to open up on a ward. As the non-ill party you tend to try to do whatever you can to raise a smile on the face of the person you love who hasn't urinated for 72 hours, or whatever fresh hell it is that's led you to hospital this time! These things were definitely as important to me as the trauma and pain of that period in our lives so it was something I really wanted to include in the book.

JU: How did you cope with 'reliving' or 're-experiencing what you were both going through when recollecting events for the story?

DB: A lot of what the book is about is coming to terms with being chronically ill and disabled and the ways in which this affects your interactions with the world. Because this is still ongoing and a lot of the things I covered in it are still everyday occurrences (travelling on public transport while disabled does not get any easier the longer you've been doing it and I still somehow seem to manage to get into an altercation with someone every time I travel with Hannah!) it didn't feel so much like 'reliving' as just transcribing our lives onto a page. The only time I did get a bit emotional was the first time I read the whole book in it's printed form. There was a bit of time between finishing up the artwork and having the finished thing in my hands, so it was the first time I felt any level of remove from it and could experience the book and the events separately from writing / drawing them. It was a good kind of emotional though I think!

"I hope that the book will offer some insight into a world that I know I had next to no knowledge of until it directly affected my life."

JU: How do you feel/hope this particular project will resonate with those that read it?

DB: I hope that the book will offer some insight into a world that I know I had next to no knowledge of until it directly affected my life. As well as that though my hope would be that the overwhelming takeaway would be a story of mundane yet beautiful love between two people, in spite of the hurdles that are put in their way. Also, if it stops just one able-bodied person from sitting in the priority seats on a bus or a train then I'd consider it a victory!

'There's Only One Place This Road Ever Ends Up' is out now and available in both digital and physical format via David Biskup Books. Also be sure to check out David's portfolio here

All imagery copyright David Biskup © 2020

Just Us Newsletter

Get your regular dose of insights and news from Just Us, straight to your inbox.